How Much of the World's Carbon Emissions Come From Beef

As I have shown before, there are large differences in the carbon footprint of unlike foods. Beefiness and lamb, in detail, have much higher greenhouse gas emissions than chicken,pork, or plant-based alternatives.

This data suggests that the most constructive way to reduce the climate bear on of your diet is to eat less meat overall, specially red meat and dairy (see here).

Metrics to quantify greenhouse gas emissions

In this post I desire to investigate whether these conclusions depend on the item metric nosotros rely on to quantify greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. It could be argued that cerise meat and dairy take a much higher footprint because its emissions are dominated by marsh gas – a greenhouse gas that is much more potent merely has a shorter lifetime in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. Methane emissions take and then far driven a significant corporeality of warming – with estimates ranging from around 23% to forty% of the total – to appointment.1

In the box at the end of this article I discuss the debate on emissions metrics and the treatment of methane in more detail. Just, here, I'll proceed it short:

Since in that location are many dissimilar greenhouse gases researchers oftentimes amass them into a common unit of measurement when they want to make comparisons.2 The nearly common way to do this is to rely on a metric called 'carbon dioxide-equivalents'. This is the metric adopted by the Intergovernmental Console on Climate Change (IPCC); and is used as the official reporting and target-setting metric within the Paris Agreement.3

'Carbon dioxide-equivalents' (COtwoeq) aggregate the impacts of all greenhouse gases into a single metric using 'global warming potential'. More than specifically, global warming potential over a 100-year timescale (GWP100) – a timeframe which represents a mid-to-long term period for climate policy.

To summate CO2eq ane needs to multiply the amount of each greenhouse gas emissions by its GWP100 value – a value which aims to represent the amount of warming that each specific gas generates relative to CO2. For example, the IPCC adopts a GWP100 value of 28 for marsh gas based on the rationale that emitting one kilogram of methane will take 28 times the warming impact over 100 years as one kilogram of CO2.4

Methane is brusk-lived, CO2 is long lived: this makes aggregation hard

To understand why the conversion factor of 28 is criticised one needs to know that dissimilar greenhouse gases remain in the temper for dissimilar lengths of time. In contrast to COtwo, methane is a brusk-lived greenhouse gas. Information technology has a very strong impact on warming in the short-term but decays fast. This is in contrast to CO2 which tin can persist in the atmosphere for many centuries.5 Methane therefore has a high impact on warming in the short term, but a low touch on in the long run. This means there is oftentimes confusion as to how nosotros should quantify the climate impacts of methane.

Researchers therefore develop new metrics and methods with the aim to provide a closer representation of the warming potential of dissimilar gases.

Michelle Cain, Myles Allen and colleagues at the the Academy of Oxford's Martin School atomic number 82 a enquiry programme on climate pollutants, which takes on this challenge. Dr Michelle Cain, ane of the lead researchers in this area, discusses the challenges of GHG metrics and the role of a new way of using GWP which accounts for methane'south shorter lifetime (chosen GWP*), in an commodity in Carbon Brief hither.

Methyl hydride's shorter lifetime ways that the usual CO2-equivalence does not reverberate how it affects global temperatures. And so CO2eq footprints of foods which generate a high proportion of marsh gas emissions – mainly beef and lamb – don't by definition reverberate their short-term or long-term bear upon on temperature.

How large are the differences with or without methane?

The question and so is: Do these measurement issues thing for the carbon footprint of different foods? Are the large differences only because of methane?

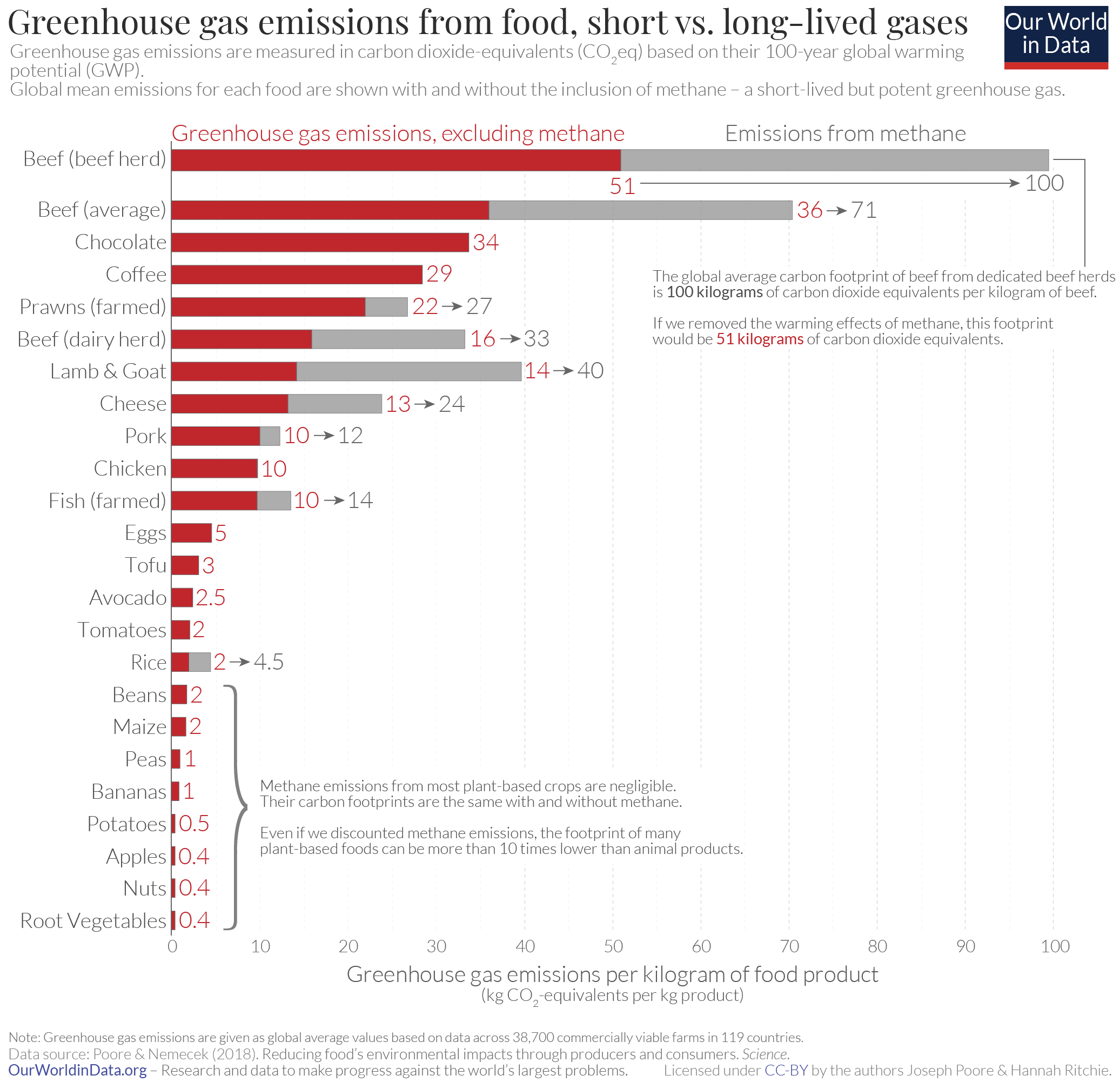

In the visualization I compare the global average footprint of different nutrient products, with and without including methane emissions.half dozen

Equally in my original post, this information is sourced from the largest meta-analysis of global food systems to date, by Joseph Poore and Thomas Nemecek (2018), published in the periodical Scientific discipline.7 The report looks at the environmental impacts of foods across more than than 38,000 commercially viable farms in 119 countries.

This chart compares emissions in kilograms of COiieq produced per kilogram of food product.

The red bars evidence greenhouse emissions nosotros would have if we removed methyl hydride completely; the grey bar shows the emissions from marsh gas. The crimson and gray bar combined is therefore the total emissions including methane.

As an example: the global mean emissions for one kilogram of beef from non-dairy beef herds is 100 kilograms of CO2eq. Methyl hydride accounts for 49% of its emissions. So, if nosotros remove methane, the remaining footprint is 51 kgCO2eq (shown in red).

As we see, marsh gas emissions are large for beef and lamb. This is because cattle and lamb are what we call 'ruminants', in the process of digesting nutrient they produce a lot of methyl hydride. If nosotros removed methane their emissions would fall by around one-half. Information technology also matters a lot for dairy production, and a reasonable corporeality for farmed shrimps and fish.

This is non the example for plant-based foods, with the exception of rice. Paddy rice is typically grown in flooded fields: the microbes in these waterlogged soils produce methyl hydride.

This means that beef, lamb and dairy products are peculiarly sensitive to how we care for methane in our metrics of greenhouse gas emissions. Few would argue that we should eliminate methane completely, merely, as explained, there is an ongoing debate equally to how to weigh the methane emissions – whether the grey bar should shrink or abound in these comparisons.

So is it true that scarlet meat and dairy just has a large carbon footprint because of marsh gas? As the cherry bars show information technology is not.

Although the magnitude of the differences alter, the ranking of different food products does not.

The differences are still large. The average footprint of beef, excluding methane, is 36 kilograms of CO2eq per kilogram. This is still virtually iv times the hateful footprint of chicken. Or 10 to 100 times the footprint of most establish-based foods.

Where do the non-methane emissions from cattle and lamb come from? For most producers the key emissions sources are due land utilize changes; the conversion of peat soils to agronomics; the land required to grow animal feed; the pasture management (including liming, fertilizing, and irrigation); and the emissions from slaughter waste.

What about the impact of producers who are not raising livestock on converted country? Do they have a low footprint? In our related commodity I look in detail at the distribution of GHG emissions for each production, from the everyman to highest emitters. When nosotros exclude methyl hydride, the absolute lowest beef producer in this large global dataset of 38,000 farms in 119 countries had a footprint of 6 kilograms of CO2eq per kilogram. Emissions in this instance were the effect of nitrous oxide from manure; machinery and equipment; send of cows to slaughter; emissions from slaughter; and nutrient waste (which can be high for fresh meat). 6 kilograms of COtwoeq (excluding methyl hydride) is of course much lower than the boilerplate for beefiness, but still several times college than most plant-based foods.

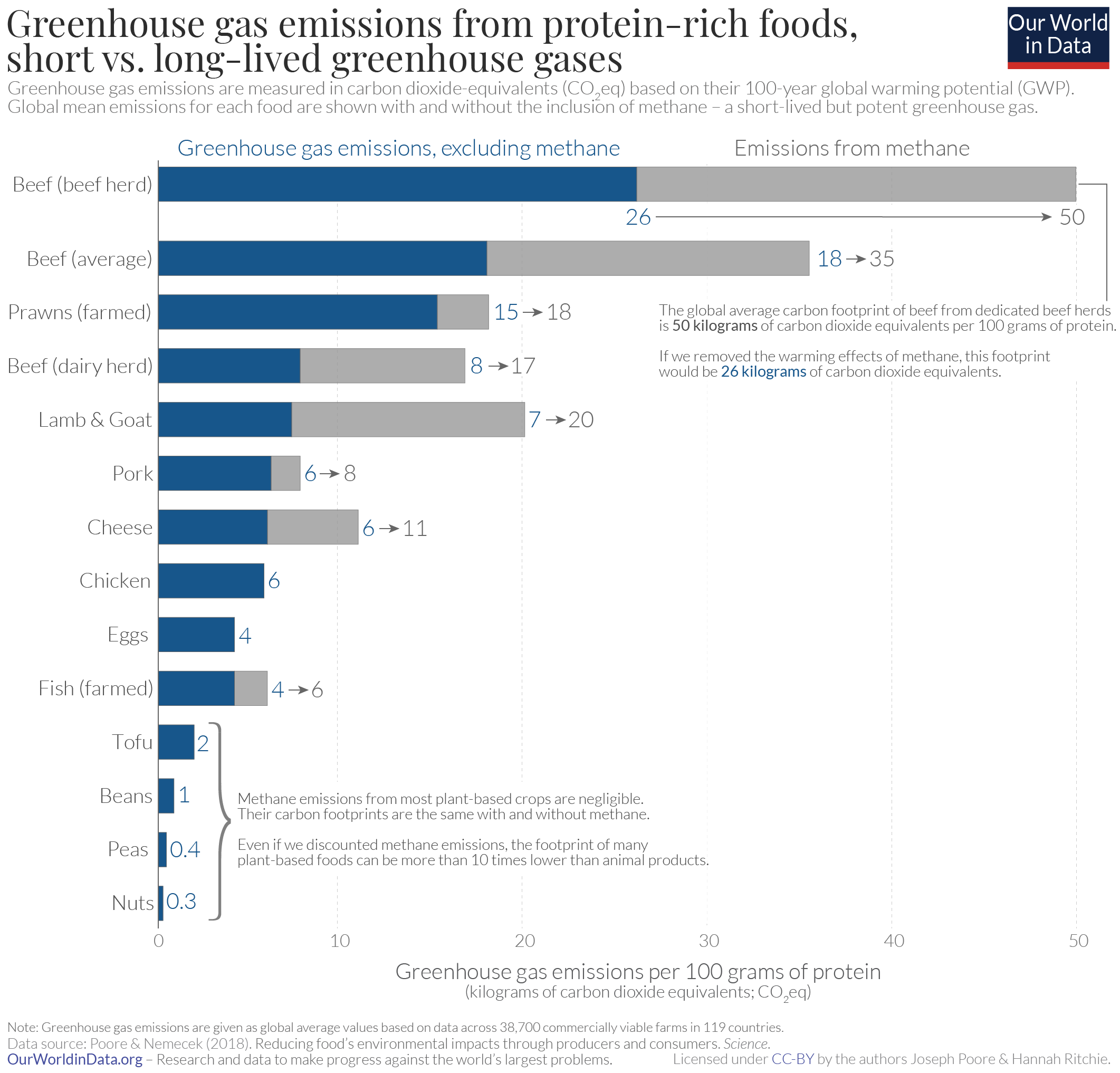

Comparing the footprints of protein-rich foods

Is information technology perhaps misleading to compare foods on the footing of mass? Afterward all one kilogram of beef does not have the same nutritional value every bit one kilogram of tofu.

In the other visualization I therefore show these comparisons as the carbon footprint per 100 grams of poly peptide. Once again, emissions from marsh gas are shown in grey; only this time, emissions excluding methane are shown in blue.

The results are again similar: even if we excluded methane completely, the footprint of lamb or beef from dairy herds is five times higher than tofu; ten times college than beans; and more than xx times higher than peas for the same amount of poly peptide.

The weight nosotros requite to methane matters for the magnitude of the differences in carbon footprint we run into betwixt nutrient products. Still, it doesn't change the general conclusion: meat and dairy products all the same top the listing, and the differences between foods remain large.

Additional information: how to we quantify greenhouse gas emissions?

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-footprint-food-methane

0 Response to "How Much of the World's Carbon Emissions Come From Beef"

Enregistrer un commentaire